Freedom on the Inside

The third-floor theater of the Selma Interpretive Center overlooks the Edmund Pettus Bridge. From the window, I watched a family take pictures in front of the historic marker at the foot of the national landmark. Grandparents, children, and mother listened to the father read the stories of the attack on "Bloody Sunday” and of the three people murdered by troopers and racists during the two weeks of marches and protests. The sign also reads, “The arch of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice,” from the speech the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King made on March 25, 1965 before 25,000 people at the Capitol in Montgomery.

The video is footage of the three marches on the bridge that were filled with brutality, hatred, strength, and hope. As the video ends, a man who had walked to Montgomery 53 years ago asked the question, “What about you? What would you stand up and give your life for today?” I had no answer and watched some of the family holding hands as they walked back across the bridge that is now a symbol of freedom, peace, and rights won. Did they ask themselves the same question? Did they have a better answer?

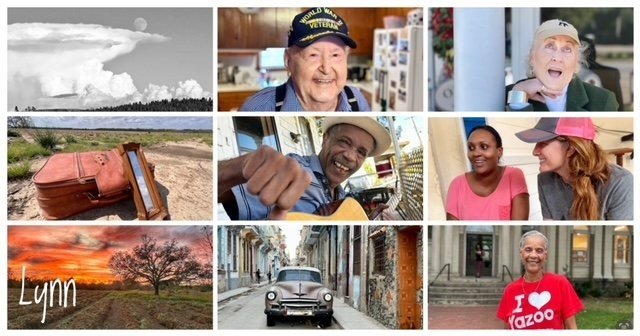

Around the block, a sign said "Art Camp" in front of Charlie "Tin Man" Lucas' studio. I walked in hoping art would chase away my guilt. The warehouse, lit by skylights, is filled with canvas spirits painted with house paint and sculptures of mummies, motorcycles, dinosaurs, soldiers, brothers, and trucks made from metal and tossed out trash.

Saying, "Yes. Yes. Yes,” Charlie walks past tables of students, encouraging them to do more as they glue Mardi Gras beads, clothespins, and scraps of cloth onto golf balls, wood blocks, pieces of garden hose, and screws pulled out of the treasure boxes.

Charlie says he has taught more than 3,000 students that art comes from inside themselves and junk can be turned into treasure. It is a lesson he learned from his grandmother as she lowered him on a rope into a deep ditch close to her farm, where he dug through trash to find things they could use at home or turn into art. His first pair of Converse tennis shoes came from that ditch.

Teaching the freedom of art and the play of creativity, Charlie builds something every day and describes it as "making a toy." This creative playing keeps his mind and spirit free. He left home at age 13 with $2.50, a jar of peanut butter, and a box of crackers because he couldn't stop making things. And, he had to get away from the people who didn't believe in him and the family who told him he couldn't do it.

Known as the "Tin Man," he is famous for making sculptures from discarded tires, brooms, hubcaps, bottle caps, hats, gloves, gears, rakes, barbed wire, and the bottom of a car. Each piece tells a story and many are about his family. His grandfather was a basket weaver and horses and dinosaurs are made from weaved metal. His great-grandfather was a blacksmith and each wheel used is in his honor. The quilts are for his mother, a quiltmaker who once used her quilting needles to reattach his thumb. He was four years old and almost sliced it off when he fell onto an empty can of Spam. The scar still stretches across his palm

As Charlie talks, 66 years of stories come out fast. Stories of whippings for making things from what the family was picking in the field instead of filling his basket. He was seven years old and forced to watch the four younger children and cook each day for the family of 20.

There are stories of dropping out of school in fourth grade, living in abandoned houses and making art that people didn't understand. He built hot rods and houses even though he struggles with dyslexia and words that "won't sit still." He laughs about going dumpster diving and eating lunch in graveyards with his neighbor and friend, the late storyteller Katherine Tucker Windham.

After he left home, he worked in a variety of jobs in construction and the fields. He married and had seven kids, but struggled with his art. He says he didn't know how to inject energy into people to help them see the art in what he was doing. Sometimes he didn't understand what he was making, either.

In 1985, a broken back, a prayer, and a vision from God freed him from the old Charlie Lucas and the Tin Man became a new part of himself. Confined to his bed after an accident loading lumber on to his truck, he prayed for a way to reinvent himself. God answered with a vision for his art that would take him around the world. He would write books and become a teacher, but the vision told him he would also lose his wife and kids, but not through death.

The next morning he woke up with $10 in his pocket and invested it in welding rods and his career. His family thought he was crazy and tried to send him to a mental hospital, but Charlie promised God he would do it all with a humble heart. The vision was right, Charlie has taught at Yale, had exhibits in France and Italy, and has been in many books, including a history book in Alabama schools.

“My wife left me 107 times and took my babies from me. I cried and made things, cried and made things. It is just me and my dog now and she is cheaper than a wife.”

Charlie says his art comes from the rawness inside. "When you are educated from the inside, you know what is there and the truth comes out."

“When It comes from the inside, you are free and don't have to worry about making it look pretty for someone else," he says. "I polish myself every day and can walk out in the world and be honest with myself. I don't have to worry about anything in the back or the front of me. I am living this day. Tomorrow is icing on the cake.”

Charlie defines freedom as walking into the world and being honest with yourself. Living who you are from the raw truth inside.

The Tin Man gave me my answer. Freedom for each of us -- Charlie, the family on the bridge, the kids gluing beads, you and me -- to be our honest selves from the inside instead of being forced by the government, society, or our families to be someone else on the outside.

That Is freedom worth dying for.