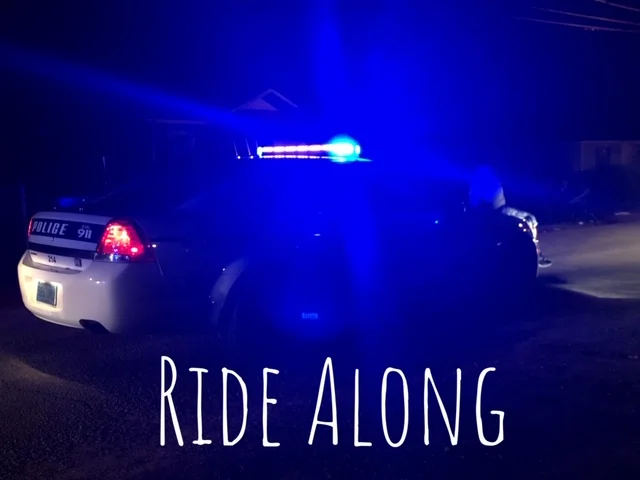

Ride Along

The shift for squad 2 in Precinct 1 begins at 5:30 p.m. with a squad meeting, as Lieutenant Reidy goes through his list for the night.

Reidy (everyone calls him LT), has been on the force for 40 years, and retirement is coming soon. He tells his squad to be on the lookout for a silver Jeep that “hit” several Dollar Generals the night before and he wants extra attention on all of the stores. There are also warnings of a suspicious character on one street seen the night before, and neighbors who need to be separated.

Sergeant Paul Hosford stops by to thank the squad for the work they do, and gives a pep talk in front of a poster of the Mobile skyline that reads, “Our mission is to make Mobile the safest city in America with respect for everyone.”

“We are the referees out there,” Hosford says. “Take an extra two to three seconds to think about what to do. If the hairs go up on the back of your neck, then don’t do it. Keep it fun and protect each other. My main concern is that you get home.”

LT assigns me to officer Matt Towey and describes him as, “The one who uses the hair gel.”

Anyone can sign up for a ride along with the police. I’m going because I want to witness a domestic violence call. They assure me this will be easy because domestic violence issues make up a majority of their calls.

The night shift runs from 6 p.m. until 6 a.m.. Squads alternate between night shift one month and day shift the next. Towey says the calls on each shift are different — more burglaries during the day, more patrol and criminal activity at night. And less traffic.

Precinct 1 covers Dauphin Island Parkway (DIP), the State Docks, up to Government Avenue and to the Causeway. Officers in Squad 2 say theirs is the busiest, toughest precinct in the city and they are proud of the work they do here. Towey puts about 100 miles on his white Chevrolet Caprice every shift.

Our first call out of the precinct headquarters on Broad Street is a burglary off DIP. The robber ran out the back door as the woman walked in the front. We race to the neighborhood with the lights and sirens on. It is an adrenaline rush and a reminder to give police cars plenty of room. Vehicles pull to the sides as we race through the neighborhood because the faster the police get there, the better their chances of catching the robber. Towey and Officer David Reyes search abandoned houses nearby. Gloves on, guns out, they cautiously approach each door, unsure of what is on the other side or in the woods behind the fence.

On our way to the house, Towey told me he is a single dad raising a son and daughter, ages 8 and 7. He is grateful for his parents, Matt and Jessica Towey, friends and nanny Morgan Lassiter who take good care of his kids while he is away. Wanting to be cop since he was three years old, Towey went into the Coast Guard for 10 years to prepare himself. He has been on the force for over a year and says he wants to make the world safer for his kids. He also wants them to be proud of their dad.

Those two kids are all I can think of as Towey and Reyes cautiously approach the first door of a house with the windows broken out. This isn’t a TV show. It’s real men with families waiting for them to come home.

Please God, don’t let anything happen to them.

The two houses they searched were empty and we had to leave for another call, but I said that prayer all night. Towey says every stop is a risk and rarely what it seems to be. An expired tag can become a bust of guns, drugs, or someone with a warrant out for their arrest. Any dispute can turn violent.

The victims become personal, too. At the robbery, the mama, still wearing her name tag from work, stands in front of her house hugging her son and daughter, dressed in their school uniforms, waiting for the officer to tell them it is clear. How will it feel to walk into her house after the police leave? How will they get to sleep that night? Will she ever feel completely safe in her own home again?

The first calls started out easy but got harder as the night went on.

The next stop is for disorderly conduct in a cul-de-sac where neighbors watch out for each other. Two teenage boys who didn’t live there were causing problems and were told to leave. As they walked away, one boy said, “We are going to make you pay.” A few minutes later, they began shooting fireworks at the houses from a street behind the trees.

The popping sounds and gray smoke lead to the boys and two paper bags of fireworks in a front yard. Towey and Reyes walk up to the door of each boy’s house to talk with their parents. An angry mother tells her son he can’t leave their yard without her knowing about it. Watching her son pay no attention, Towey tells him to show respect to his mother and his neighbors.

Driving away, Towey says the boy demands to be treated with respect, but doesn’t respect authority — a frequent problem. The parents call the police to control the kids, but there is little police can do beyond warnings and arrests. Police can’t take on the role of parent. When he’s working the day shift, Towey spends much of his time dealing with issues at Williamson High School and trying to teach respect to students, especially towards their teachers.

The ride along shows adults need to grow up and act respectful, too. The next call is a complaint about a neighbor throwing trash out of a second-floor window. As we pull up, an old man watches us from above. Standing among the discarded wrappers from hamburgers, fries and an assortment of other trash, Towey and Reyes call him down to hear both sides of the problem. The old man rolls his eyes as Towey speaks.

“You are acting like a 12 year old rolling your eyes and throwing trash at him out of your window,” Towey says. “You are both grown men and should know how to take care of problems like this on your own without calling us to solve it for you. You are taking our time away from people we need to help.”

As he drives away, Towey talks about preparing for each call. He runs scenarios through his head about what could happen and rehearses them so he steps out of the car prepared.

“Every call is different. Different partner, different time of day. Being prepared makes a difference in a split-second decision. I also like the excitement, and knowing, each day, I made life a little better for someone.”

Towey is from a military family and calls them “very patriotic.” These are the values he clings to on the hard days when the paperwork is overwhelming and takes too much time, or when criticism makes the job harder than it should be.

During a break between calls, Towey and Reyes talk about the dangers of their job. They know the risks, but don’t dwell on them. There are shootouts and times they have to run towards the gun. They do what has to be done and trust their lives to each other. Afterwards, they decompress, learn from it, then shake it off. Sometimes, dark humor helps them through.

Towey says a hard job has become even harder as police are under intense pressure to do their jobs right, and, they’re under public scrutiny, often with the media portraying them as the bad guys. He was cleared last year of shooting a man stabbing his wife while the couple was trapped in their overturned car after an accident.

“I know if I do one thing wrong, I am done,” he says. “That is why the enrollment is dropping at police academies. Police officers are human and have to make split-second decisions between life and death, and then keep going. You never know what happened on the call before they pulled you over.”

As we patrol the R.V. Taylor housing project, a woman looks at us and says, “They know what just went on here.” We don’t, but I wonder what she means.

On our way to a possible domestic violence call, we are redirected to a robbery in the parking lot of a Waffle House. The victim smokes, and gives a vague description of a man in a black hoodie who asked for a cigarette, but then stole his phone and cash and ran towards Dauphin Island Parkway. We drove through neighborhoods looking for the robber on the run, but there was no sign of him. Every place looks like a hiding place in dark corners at 10 p.m.

“Sometimes, it is like looking for a needle in a haystack. But you have to keep looking because sometimes, you get lucky,” Towey says.

We are called back to the Waffle House because an SUV pulling out of the parking lot onto Government Street hit another officer’s car and drove off. Towey caught him and turned him back around. As he works on the paperwork and ticket for the high school student, LT shows up to see the damage and tries to buff the scratches out with a Clorox wet wipe. The car belongs to the officer they call “Mary Poppins” because she is the positive one on the squad.

As we drive past Ladd Stadium for the fourth time, the dispatcher says a man just arrived at Infirmary Hospital. He was shot behind a store on the corner of Houston and Hurtel Street, and mentioned a grey Camry. Neighbors have been complaining about drugs and violence on that corner, so Towey takes the call. He said it is hard to help in some neighborhoods because people don’t want to tell what they know to the police. But he treats people fairly and hopes to build relationships and trust.

Six young men and a woman, who appear to be in their 20’s, are standing in front of a house on the corner. Some are leaning on a grey Camry. Towey steps out of his car to ask a few questions. They say they were inside the house and don’t know anything about the shooting. Towey returns to his car, says he smells 68 (drugs), and calls for backup because that is a reason to search. While we wait, we look for shell casings or blood in the parking lot of the store. LT comes by to help and make sure we are okay.

Backup arrives, and other officers from Squad 2 separate the group between the patrol cars and gather IDs for background checks. None have outstanding warrants and all still deny any knowledge of the shooting. As officers search the area, the dispatcher says the shooting victim gave the names of three men. Three of these guys.

Towey is right. Sometimes a call starts out small and grows into something much bigger. Sometimes the cops get lucky.

Searching under, in and around cars, the squad gathers evidence and gets closer to the truth as they find burner phones and a small digital scale to measure out drugs. Bags of marijuana are stashed in the bushes and spice is hidden in the mailbox. They find Ziploc bags, a banana clip, and a box of ammunition in the trunk. There are shell casings behind the hood and a medicine bottle with one Oxycodone in the car. There is $600, mostly in $20 bills, in one pocket and $1300 in another.

An officer crawling beneath the cars finds a Glock and an AK-47 behind the tires. Towey says a bullet fired from a rifle like that can cut through his bullet-proof vest as easily as a knife cuts through butter. Bags of weed are found in the trunk of another car parked in the driveway. The one who drives this car lives in the house with his grandfather and mother. Both are watching from their yard, but say they didn’t hear the gunshots either.

The mama stands in her housecoat and quietly takes it in. The grandfather says he works for Waste Management and has to be up at 4 a.m. to go to work.

“I deal with everyone else’s garbage,” he says. “From dead dogs to newspapers, I push it all through.”

A narcotics officer arrives. Tonight he is on call and working on overtime. He takes notes before leaving to pick up prostitutes.

Inside the Camry, the clock says 12:30 and the radio plays NBA YoungBoy “2 Hands (4 Respect).”

“On the block with a Glock hangin’ out the Bentley

Gotta flex and I swear I’m gonna make ’em feel it

Out the top of the drop when I let off the semi

Wanna live like this here? Be a part of the business

Wanna come like this here? Better change yo’ attendance

In that order I’m a chief did I mention

Detergent washing’ like dirty laundry

While workin the corner, caught us some weight, servin’ the moment

We baggin’ up zips, safety pin breakin’ whoever want it.”

Neighbors come out. Another mama clutches her chest below the cross on her necklace and cries. She paces and pulls at her short hair until Towey allows her to walk to the car and talk to her son through the bars of the window.

“Little boy. Little boy. I told you not to do this,” she says. She scolds him for not carrying his pistol permit and understands when Towey tells her she can’t get it for him. She yells at her son and tells him to stop talking when he tries to talk back to Towey.

Towey lists for her the charges that all seven will face: Possession of Marijuana 1st degree; Possession with Intent to Distribute; Possession of a Concealed Weapon; Possession of Drug Paraphanalia. They found six ounces of marijuana. Anything over five ounces makes it a felony.

The mama listens and knows her “Little Boy” could go to prison.

She says “I love you, baby” and walks away to lean on a fence and cry.

The mother in the housecoat takes her son’s Hilfiger baseball cap inside the house.

Towey hears that the victim was shot in the arm and the leg but will be okay. The identity of the shooter is unknown, so Towey guesses the shooting was over a drug deal or gang related.

As we drive the young woman to Metro jail for booking, her hands, with long blue and pink nails, are cuffed behind her back. Towey tells her to stay away from those men and find herself a better group of friends. She says nothing except that the handcuffs hurt.

At 3:30 a.m., after the evidence is turned in and an hour of paperwork completed, Towey says the night is a win for them.

“It is likely the guns were going to be used in a retaliation shooting. We may have saved lives tonight, but we also got guns and drugs off the streets. I hope this shows that neighborhood that we are here for them and want to help.”

I never got to see a domestic violence call, but I did get to watch a win for a team that takes care of each other and cares about their precinct. Squad 2 made life a little better one more time, and all got home.

Thank you, God.

Anyone can do a ride along. Just go the precinct headquarters and submit the paperwork. The police encourages the public to ride with them and see what they do. It will open your eyes and make you appreciate how much these men and women do.