Protection From Violence

Domestic violence calls begin with a 911 dispatch announcing a “39,” followed by a description of the action and location, assigning it to the closest officer in the area. Thirty-nines are the most dangerous calls for law enforcement. As unpredictable emotions run hot, officers are often treated as a tool each side uses to win. Returning to the same homes over and over, policemen describe it as “another night, another fight.”

In larger Alabama cities approximately 60 percent of 911 calls are related to domestic violence, according to Steve Searcy, law enforcement training coordinator for the State Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Officers say it can be difficult to tell which partner is the aggressor.

“The victim calls 911 because she wants the situation to stop. She wants an officer to fix the abuser and change him back to the person he was the day they met,” Searcy said. “No one can do that. Police are there to do the job they are required by law to do.”

If there is an injury, the law requires an arrest, even if the victim doesn’t want the abuser taken to jail. Situations become volatile, quickly, and law enforcement called to end the violence becomes the enemy for interfering.

“We are the arbiter and mediator,” Officer John Druell said after he watched a man load a big-screen TV and clothes into the back seat of his car and drive away from his ex-girlfriend’s apartment. “The boyfriend called 911 because he wanted us there as he moved out. An argument escalated and our presence prevented it from getting worse. It ended peacefully.”

Druell’s second 39 of the night was from another man as his ex-girlfriend banged on the doors and windows of his home protesting a warrant he signed for her arrest. She wanted him to drop the charges of stealing his things because her court date was coming soon. “I am not taking her back,” he said. “As soon as she got on the crack, she had to go.”

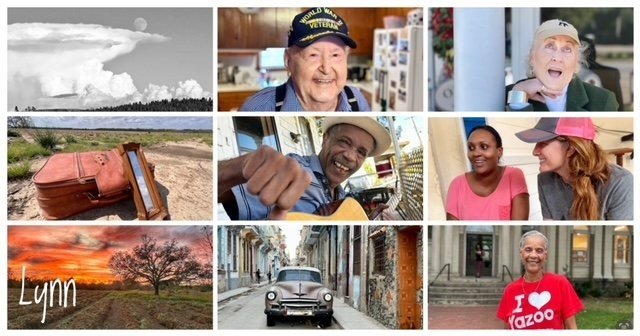

Druell said calls come from men and women, black and white, couples gay and straight. Partners in any relationship can get abusive fighting over finances, kids, infidelity or what one thinks the other should have done.

Brittany, who survived an abusive stepfather, boyfriend and husband, said her young son saw her boyfriend sitting on top of her, choking her. The boy said, “Please don’t hurt my mommy.” That was the first time she called the police and her boyfriend went to jail.

“He went to jail four times while we were together,” she said. “His brother bonded him out and I dropped the charges. Each time he came back begging and crying. Saying he loved me and just wanted to take care of me. I was one of those women who believed and went back. My family told me if I went back, they were done. The people living around me knew that I had a baby daddy knocking on my windows every night. The police finally said, ‘If you call us again, we are taking you both in.’”

Police go to some houses many times, but in each call their job is to calm the situation and get the victim to safety, Druell said. “The abuse gets progressively worse and a 39 could become a 19 (domestic violence homicide).

“We do our job the best that we can,” he said. “We can’t control what the victim or abuser does next.”

Police officers can’t always control what happens to themselves, either. Officer Justin Billa of the Mobile Police Department was killed February 20 when responding to a domestic violence homicide call. The abuser killed his ex-wife and later killed himself.

“Domestic violence killed Justin,” Erin Billa, Justin’s wife said. Erin is raising their almost 2-year-old son on her own and promoting police and community relations through the Justin Billa Foundation. “The abuse doesn’t just affect the family involved, it affects the whole community. Maybe Justin’s death helps raise awareness of how dangerous these calls are for police. A reminder that they are human and have families waiting for them at home.

“They are doing a job no one else wants to do.”

That job no one else wants to do is on the front line of an interconnected system of lawyers, judges, shelters and advocates helping victims to a safer life -- a system victims may be unwilling to enter, or stop-and-start many times. The legal system is the next step after an arrest with domestic violence misdemeanors tried in municipal court and felonies in district court.

Domestic abuse cases are tried one day a month in Judge Jill Phillips’ district court in Mobile. The prosecutor for the district attorney’s office stands on the right side of the courtroom representing the victims. Attorneys for defendants take their turn on the opposite side. A victim’s name is called, often followed by no response. The prosecutor asks for a reset and the judge gives the victim one more chance to appear.

In some cases, the defendant takes the stand and walks out when there is no victim. Some couples enter together, the victim drops the charges, and they walk out together holding hands.

Victims dropping charges and abusers going free are frustrations for each player in this system of protection. There are also “victimless prosecutions” where the case is prosecuted without the witness. This is done for the victim’s protection, and the system stands up for her when she can’t stand up for herself.

“Even if we have strong evidence, the harder part is encouraging the victim to make the abuser accountable for his actions,” Mobile County District Attorney Ashley Rich said. “We know if we don’t get him now, both of them are going to be in our court again. This is a hard process for the victim. She may not want to leave him or he may be threatening to hurt her or her family if she goes through with it.”

Victims receive a counselor from Penelope House (from the Lighthouse in Baldwin and surrounding counties) and the district attorney provides victims’ advocates to empower them to use their voices.

“We are asking the witness to go on the stand and re-victimize herself by telling her story,” Rich said. “That is even harder if it goes to trial in front of a jury of strangers. But if we don’t do this, we can’t put away the perpetrator and he will do this again to the victim or to someone else.”

Judge Phillips said leaving is a process, not an event, but the abuse will continue if the defendant walks out free.

“We had one case where the guy got off and murdered a woman in his next relationship,” she said. “Maybe we could have prevented that death if the victim had pressed charges and sent him to jail.”

Court advocates try to build trust and support, making multiple attempts to get the victim to court. They explain the court process, her rights, and the resources available. They also provide a safe escort and prepare her to face the defense attorney during cross-examination.

“Courts are intimidating and another language that needs to be explained,” Kristen Clikas-Murphree, supervisor of the Court Victim Advocate Program at Penelope House said. “We prepare victims for the personal and difficult questions that the defense attorney will ask. The victim already feels like the abuse is her fault and has to go up against an attorney paid to discredit her as a witness. That is hard for any person to do.”

Court is one step in a difficult process. Leaving an abusive relationship is the most dangerous time for a victim, but the arrest and release of the abuser is also a time of control and revenge. The perpetrator can bond out and be back home a few hours later, sometimes before the victim leaves the hospital.

“When we arrest and take the abuser away, we give the victim information about Penelope House and tell her to get out because he is going to be angry and likely to retaliate when he comes home,” Druell said.

If the arrest is a misdemeanor domestic violence in the third degree (the catch-all for most domestic violence cases), bail is typically set by the municipal judge or magistrate at $500 to $1,000 and the perpetrator can bond out for $50 to $100. Bail ensures the defendant will appear in court, but it is not a punishment because he is innocent before proven guilty. Low bails are intended to be fair to poor defendants. However, advocates and law enforcement say a higher bail for domestic violence can give the abuser time to cool off in jail and be a deterrent to future behavior.

“The bond schedule in Alabama is pitiful,” Searcy said. “He can get a misdemeanor domestic violence third for assault for beating the hell out of someone, bond out for $50 to $100 and be home while she is still in the hospital. It is a slap on the wrist and he will do it again. Raise the bail and it won’t be so easy for friends or family members to get him out each time.

“It gives him another reason to rethink his actions.”

Almost every day The Lighthouse shelter sees someone hurt because the perpetrator got out on bond, Rhyon Ervin, executive director of The Lighthouse of Baldwin County said. “That damages the victim’s confidence in the system that was supposed to protect her and she will not trust the system.”

The third misdemeanor conviction is now an automatic felony, but it takes the awareness of officers, victims and advocates to keep count of the charges. A felony means jail time, but victims and some in the system of protection describe jail as a revolving door.

“An overcrowded system affects how much time domestic violence offenders will actually serve, and they are right, it is a revolving door,” Spiro Cheriogotis, a former assistant district attorney recently elected to District Court Judge said. “Metro Jail and the Alabama Department of Corrections have different calculations. Most offenders who are sentenced to jail time at Metro serve at least half of their sentence before they are eligible for release. Some felony offenders get a 15-year sentence and are out in two years and abusing victims again. Prisons need to be reformed.”

A victim can help herself by getting a protection from abuse order (PFA) from the court, which provides protection against current or former intimate partners. Violating the PFA is a crime, even if the behavior isn’t, and the abuser can be arrested before he has a chance to hurt the victim. In Alabama, the abuser can’t possess a firearm if he has a misdemeanor domestic violence conviction or a PFA against him.

“A PFA is a piece of paper, not a bulletproof vest, and victims still need to avoid circumstances and be safe,” Clikas-Murphree said. “It may not stop the abuser, but the punishment is greater and it empowers victims to be a little less afraid.”

Searcy acknowledges that getting the PFA is a dangerous time for victims. “Domestic violence is a continuation crime,” he said. “A protection order means he lost control to the court and he will fight to get that control back.”

Victims feel guilty about putting their abuser in jail, believing it is their fault and they are the ones who need to change, said Ervin.

“Families and friends will blame her, too, but she doesn’t have the power to put him in jail,” she said. “His behavior put him in jail. I tell them if a stranger beat you and treated you like that, you would have no problems putting him in jail.”

All parts of the system say mental health is a missing piece that could make their jobs easier. Budget cuts reduced mental health services and closed inpatient facilities so emergency rooms are now used for stabilization during a psychotic event.

“Women come to us in a suicidal or paranoid state and we send her to an emergency room for help. They send her back out, temporarily stabilized, but there is no treatment for what got her there,” said Ervin. “Mental illness makes you more susceptible to domestic violence.”

The emergency room is also an invisible side of the system of protection. Victims are brought into trauma units after a stabbing, gunshots, burns or being pushed out of a car and run over. They come in with rib and facial fractures, or have been hit so hard it hurts their internal organs or they have brain bleeds.

“We see the worst sides of domestic violence, but patients don’t open up about what happened or who did this to them,” Ashley Williams, a surgeon in her fourth year of residency at USA Health University Hospital said. “We have case managers and social workers who help with what happens next, but Alabama is one of the few states that does not have a mandatory reporting law. Physicians don’t have to notify police when one of these cases comes in.”

Hospitals may not have to report abuse to police, but the doctors, nurses and other staff understand the cycle of domestic violence they are pulled into.

“We look at trauma patients as having a disease. If it happens once, the risk is higher that it will happen again,” she said. “If she doesn’t change the environment or behavior, she ends up back here with us trying to save her life again.”

That means all parts of the system will be trying to save her life again.

A note from the author: The system of protection helps victims to a safer place but has room for improvement. No matter how good the system, there will always be “another night, another fight.” Watching victims return to their abusers and seeing the behavior get progressively worse breaks the hearts of law enforcement officials, advocates, prosecutors, doctors and judges. They question what else they could have done for each soul lost, but are motivated by the ones they helped save who are still alive today.

If you need counseling services, contact Lifeline’s Counseling Service at 251-602-0909. If you need domestic violence help, Penelope House is a shelter in Mobile that provides safety and protections for victims of domestic violence and their children. Its 24-hour crisis hotline is (251) 342-8994. The Lighthouse is the shelter in Baldwin County and the number for its crisis line is (800) 650-6522. You can also call 2-1-1 to find the help you need anywhere in Alabama.

The series “From Hell to Hope” ran in Lagniappe in October 2018. It won first place in Best Feature Writing Coverage in 2019 from the Alabama Press Association.