If any of those bullets had hit differently, I would not be here today

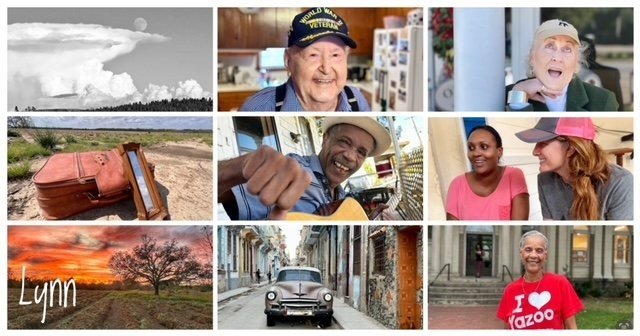

General Guy Hecker was raised by his mother, aunt, and grandmother on Springhill Avenue in Mobile. He was about 15 the first time he flew in an airplane. The pilot was a friend who had taken only a few flying lessons.

“He didn’t know any more about flying than a man on the moon,” Hecker said. “I must have been crazy to crawl into that old World War II bi-plane with him, but I was hooked.”

Hecker’s boyhood hero was a cousin who flew in World War II; his own goal was to become an Air Force pilot. Hecker attended the Marion (AL) Military Institute, The Citadel Military College of South Carolina, Harvard Business School, the National War College, and the Air Force flight school. He was one of the first air training officers in the new U.S. Air Force Academy and was made an honorary member of the Class of 1959, the first graduating class at the Academy.

“I enjoyed flying so much that I decided to stay in the military,” he said.

Flying also helped Hecker court Frances, a girl from the Mississippi Delta who was a stewardess on American Airlines. He would put her on a plane at Love Field in Dallas, then fly to where her flight overnighted. Hecker had the faster plane and would beat her there.

“It wasn’t a bad way to date,” he said.

A few years later, the couple married and had three children. Hecker was a major in the Air Force and was sent to the Vietnam War, leading a group of F-100 Super Sabre jets from McClellan Air Force Base in California to Bien Hoa Air Base, a U.S. base about fifteen miles northeast of Saigon. Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine units were stationed there from 1961-1973

Hecker was in charge of ten lieutenants in the 90th Tactical Fighter Squadron, the oldest squadron on continuous service in the Air Force. Called "Pair-O-Dice,” the squadron’s lucky "Seven Up" emblem was red dice with white dots reading seven no matter which way it was tallied. Pilots called their F-100s “The Hun.”

Squadron life for the Pair-O-Dice centered around a hooch built between two base runways. The hooch was living and maintenance quarters. A small mess hall on the alert pad cooked up anything the pilots wanted.

“They had great steaks. That was the advantage of being on alert,” Hecker said. “I would order my steak with an over-easy egg on top.”

Every night, a flight crew was on the alert pad, ready to go, or “scramble.” A TIC call with “troops in combat situations” scrambled the alert pad.

“Some guys didn't like to go on alert because it was more risky than the average bombing of the jungle,” said Hecker. “There were bad guys down there who wanted to kill us. We had to kill them first.”

One night, Hecker was “roped into” planning and emceeing a going away party for senior colonels at The Officers Club. He had a few drinks, knowing it wasn’t the Dice’s turn to be scrambled.

“Needless to say, I had a great hangover,” Hecker said. “But the call came into our squadron’s tactical air control center. The Viet Cong were coming through the wire into an Army camp. They needed napalm and bombs. Quick.”

The mission also needed someone with the most experience. One of Hecker’s students from the Air Force Academy was on duty in the command post. He saw Hecker’s name on the grease board and said, “That’s who we’ll send.”

Lynn High was part of Hecker’s team on the mission and wrote about that day in January 1969 in his book, Born to be a Warrior.

At 4:00 a.m., the claxon rang, and the duty officer shouted, “Scramble the Dice!”

Everyone was awake, the claxon’s shrill scream allowing no one to sleep through it, and everyone was shocked to hear the call for the Dice…Within two minutes we were heading down the taxiway with no idea where we were headed.

The command was to head toward The Seven Sisters, a small mountain range in Cambodia: a different direction than most missions. There was no moon, and the night was black with a thick haze.

The attack was coming from a former French fort on the border in Cambodia. An Army reconnaissance outpost was trapped by heavy fire. The squadron saw the mortar and machine-gun fire but waited for clearance to attack.

“Major Hecker and I could see all of this, but until we received command clearance or until the enemy began to cross the river, we were simply holding ‘high and dry’ and waiting,” High wrote.

Finally cleared to attack the fort, Hecker went first, dropping napalm. High followed with outbound bombs into the middle of the fort. He saw hundreds of tracers pass Hecker. Three pierced the major’s plane.

“As we began our departure, the FAC (Forward Air Control) told us that all firing from the fort had ceased, and the interior of the fort had many locations burning out of control,” High wrote.

Hecker later went back to the camp and saw how close the Viet Cong had gotten.

“They were picking the VC out of the barbed wire right next to the camp,” he said. “We made crispy critters out of them. You had to dehumanize them to fight them.”

Hecker and High were both awarded the Silver Star for this mission.

Hecker served in Vietnam for a year. Service members stationed there for over six months received a freedom pass for rest and relaxation. Most went to Japan, Australia, Hong Kong, or Hawaii. Going home to the U.S. was against the rules. Hecker went home anyway.

“I got on the freedom airplane and said, ‘We’re going to San Francisco, right?”

From San Francisco, Hecker flew to Phoenix for a week with Francis and their young kids. He never got caught.

“What were they going to do? Send me to Vietnam? I was already in hell there, so I had no fear.”

Hecker said those fighting in Vietnam knew the war was unpopular and the country wasn’t behind it.

“The Viet Cong defeated the French,” Hecker said. “We should have realized those guys were in it for the long haul. We didn’t need to get involved unless we were prepared to go all out. Instead, we got involved in increments rather than using the full force of the United States. But we were afraid China or Russia would join the VC, and we'd have World War III.”

For Hecker, the Vietnam War was about flying, courage, and proving himself, not the “mundane issues of politics.”

(Today is National Vietnam Veteran Day. Gen. Hecker’s story is part of a series I’ve been doing for Mobile Bay Magazine to remember the 50th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon on April 29, 1975.)