Road Trips

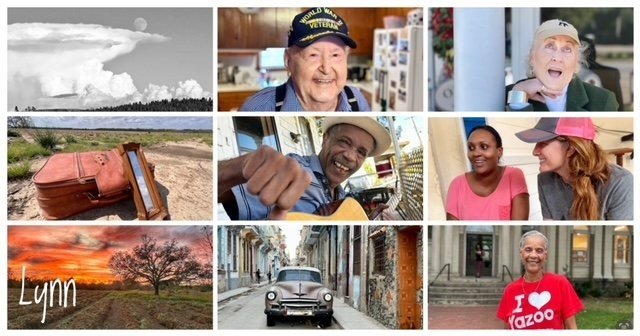

I believe in road trips. The kind with no plan. No destination. Just a bag of shorts and t-shirts, the road and time. The ones that return you home a little changed by lessons learned.

It started with my grandparents who believed travel was education, and driving was the way to go. In our younger summers, my brother Rod and I saw the U.S. from the back seat of their 1977 Lincoln Continental. It was aquamarine and came with an 8-track of the year's best country songs including "Here You Come Again" by Dolly Parton, "Southern Nights" by Glenn Campbell and "Luckenbach, Texas" by Waylon Jennings.

I was seven years old, Rod was almost five, and we played for hours on the floorboards with puppets, Hot Wheels and crayons. Each morning we left wood-paneled motel rooms before sunrise guided by AAA TripTiks to landmarks and national parks. At breakfast and lunch my grandmother slid into the back seat saying, "The kitchen is open," and stirred water into powdered milk before pouring it over puffed rice cereal. She spread peanut butter and jelly on bread a few hours later.

That was my first time to see the Rocky Mountains, Old Faithful, bison, snow and glaciers. There were murals made of corn at The Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota, and Johnny Cash played at Frontier Days in Cheyenne, Wyoming. It was also the first time I made my grandparents angry. As they had dinner at the Old Faithful Inn with food not served from their back seat, Rod and I threw cups of water from our second-floor bathroom window at a boy below. His father, the manager of the lodge, turned us in, ending my grandparents dinner. But the next day my grandfather, wearing the light blue jumpsuit he traveled in, shared his ice cream cone as we sat on a bench and watched the faithful geyser erupt. That was forgiveness.

On August 16, as we drove the last miles home on highway 432 between Benton and Yazoo City, the DJ announced that Elvis, my mother's favorite singer, died.

My mama wasn't as happy as she should have been when we walked through the door 41 years ago and she hasn’t had a favorite singer since.

My grandparents were right about the education from travel. I can't understand a place until I have seen it myself and listened to the stories of people who live there. That is why I struggle with the magazine versions of the "New South" glorifying SEC football, beach trips, Bloody Marys, barbeque and biscuits. Those are the fun parts of us, but our history is too heavy and our character is too complicated to accept an image of front porches, “y'all,” and sweet tea.

The deeper sides of the South are easy to find.

Road trips this summer started with watching the sun rise with my best friend, Kendall, on Pettus Bridge in Selma. We walked the street the marchers took 53 years ago and sat on the steps of Brown Chapel church, reading the words that Dr. Martin Luther King spoke inside: "A man dies when he refuses to stand up for that which is right. A man dies when he refuses to stand up for justice. A man dies when he refuses to take a stand for that which is true."

As we picked up the pieces of a broken Vodka bottle in front of the church steps, a man named Demetrius stopped by to help and said, "It's a shame people don't respect this area. Most people here don't even vote. We don’t stand up for anything anymore."

“We don't stand up for anything anymore” was hard to hear in the Black Belt town where thousands faced brutality, persecution and death standing up for their right to vote. During a summer of political anger from all sides, "What do we stand up for today?" became a question I asked myself over and over.

Strangers across the South provided their own answers. I watched the Bang Bang Lady, who has sold fireworks in Steele, Alabama for 21 years, and her husband Steve, an alligator hunter who sells watermelons out of the back of his truck, take in a woman who was escaping an abusive boyfriend and had no place to go.

"My door is always open. We have taken in so many people," says the Bang Bang Lady, Wanda Lamb. "We don’t meet strangers and I don’t like to see anyone hurt. I have let my bills get behind and almost lost my home helping others. It is just who I am."

In a small dress shop in Huntsville, Astrid watched a fiery revolution in Haiti on Facebook Live. Fearful for her family, she said she can't ever go back to her home in Haiti because she once spoke out against corruption and abuse.

"I am a death risk and can’t go back," she says. "I was brutally honest when I returned to Haiti to help after the earthquake and spoke out against abuse and the stealing and selling donations. I have to speak out for what is right, even if it means I can't go home. Huntsville is my home now."

On the annual July road trip with my boy, Jake, he asked to go to Blair Mountain in West Virginia, the site of country’s biggest armed uprising since the Civil War and its most violent labor insurrection. Re-listed in July on the National Register of Historic Places, the mountain where the U.S. government bombed and tear-gassed its own people standing up for their rights, will be forever protected because a small group fought for two decades against coal companies, miners and some of their neighbors to save the mountain and keep the history alive.

"Blair Mountain is a story of immigrants and miners of all colors coming together to fight for their rights," says Wilma Steele who helped found the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum and pushed to get the story recently included in history books. "I want Blair Mountain and these miners to be a reminder we can still unite together and make a difference,” she says. “We are all immigrants and aliens.”

I got to know a family of immigrants from Mexico as we repaired and painted their home on a middle school mission trip to Houston, Texas. During breaks, Alondra and her boyfriend, Dan, told stories of the dangers of living in Mexico -- his uncle was forced into a drug cartel and her sister was murdered after a robbery in December. Alondra's family left Mexico after neighbors robbed their restaurant. They moved several times but were never safe until they came to the U.S. on a green card. Her father died in heart surgery in Mexico exactly a year before Hurricane Harvey (her father had the surgery in Mexico because he had no health insurance in the U.S.).

Dan and Alondra were saved from failing schools when they were selected by lottery to get into two of Houston's college-prep charter schools. They are engineering and pre-med majors with full scholarships to Sewanee, one of the best universities in the country, but still get dirty looks because of the color of their skin (they call it mean-mugging) and are mocked for their nationality. Alondra and Dan worry about what the tightening immigration policies will do to their families and their hopes of graduating college.

How many bright, driven kids like Dan and Alondra fall through the cracks and never reach their potential because of the color of their skin, where they were born or where they go to school?

I met Tina Bojanowski, a special education teacher in Kentucky running for office for the first time because she is unsatisfied with her state's government and wants to give a voice to the vulnerable and working people that she has met in her schools.

In Prichard, Alabama, Tejuania Nelson, a preacher's daughter, opened a preschool in one of the poorest cities in the state. She is changing the community by setting higher standards for early education and giving her students and their families a better way. Across the street, Terry Gibbs is a barber who learned how to cut hair in prison and opened up his own shop after he was released. Holding his clippers, he is also a preacher, teacher, counselor, father and grandfather trying to help young guys get focused.

"One of my guys was involved in a shooting last night and it breaks my heart to know what his grandmother is feeling today," says Gibbs. "But we can’t throw our hands up and not care. There will be stumbling blocks and the depths you take others through before you cut it out. I know I was a major disappointment to my family before I turned it around."

Stacey Fleming, a former barrel racer and truck driver from Pasadena, Texas, gave up her own medical care from a car accident injury and used the money to rebuild her stepfather's home after Hurricane Harvey. Finding no help, she gutted the house, begged for materials and slowly rebuilt it by herself. Once his house was done, she became the volunteer director of Pastor’s Army and is helping teams rebuild 10 houses. They have 20 more to go.

"My stepfather was blind in one eye and raised a family of seven kids on $350 a week. I have to take care of him," she says. "I always helped people, it is who I am. I am not a receiver and hate to ask for help. If someone helps me, I have to help them somehow even if it is doing side jobs. I am hard-headed with a big heart. You aren’t going to tell me I can’t do something because I will prove you wrong.”

Proving that something can be done also drives Jerry Mitchell, the investigative reporter for the Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi, and one of my writing heroes who I met this summer. He fights injustice and deception and his reporting helped bring convictions to civil rights murders closed many years ago. Justice, even late, gives peace and closure to the families of victims but not all Mississippians feel the same way. Mitchell says the death threats give him the unexpected gift of living fearlessly.

"What would you die for?" he asks groups he speaks to. "It is not living without fear, but living beyond fear. You have to live fearlessly wherever you are. Stand up for a student being harassed or someone rejected for the color of his skin. People may hate you or try to kill you, but you have to stand up for what is right."

Interviews for the series Our Southern Souls this summer were full of people standing up for what is right. A young woman who went to law school after she protested at a Klan rally and realized she didn't have the tools to make the argument she wanted to make. A teenage boy with cerebral palsy who was bullied last year in middle school refuses to give in to limitations. He speaks out for people with disabilities and how they should be treated.

I love the South too much to pretend that it is all moonlight, MoonPies and magnolias. Each road trip shows we are a people who struggle, suffer, survive and help each other through.

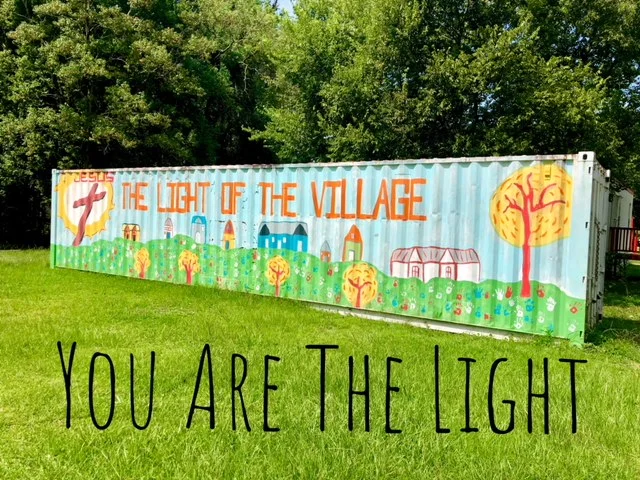

Forgiveness, fearlessness and standing up for what is right. This is a good time to get in the car and drive because there are powerful lessons to learn from the past we are trying to leave behind.