You are the Light

"If they wasn't here, I think things would be way worse. They'd be way more killings."

"Really? You think it's that important, their presence here?"

"Yeah."

"How do you think that is? I know not everybody is going to the church.”

(gunshots)

"Oh shit. God damn shots."

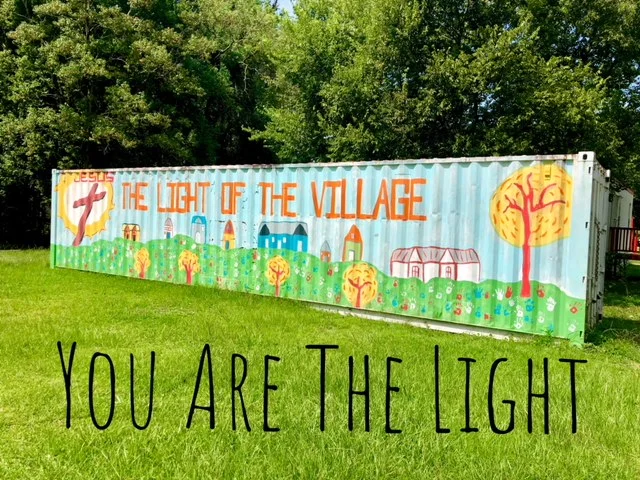

The shooting was caught on a voice recording by the writer William Guillermo Paxton as he interviewed Jesse and Da'Cino, teenage boys living in Alabama Village in Prichard, about gang violence. “They” refers to Light of the Village, a Christian ministry providing homework help, meals, love and Bible study in their neighborhood.

The gunshots killed their friend Mayo who also grew up going to the center.

Today Da’Cino has a job that got him out of the neighborhood and Jesse is leaving for his first year of college. All three boys will be featured with Light of the Village in an episode of The Good Road, that debuts on Public Television in April 2019.

On the last day of filming for The Good Road, the show’s host Earl Bridges stood in front of the center telling stories of the neighborhood. He was interrupted by gunshots a few blocks away.

"That is a small caliber pistol," he says. "We hear gunshots every time we come here. There were gunshots during the prayer and candlelight vigil for Mayo. Six months ago, Jesse’s mother was shot and killed in their house by her boyfriend.

“Can you imagine what it is like for these kids to live with gun violence every day?"

Alabama Village is a rare domestic story for the show that features good works around the world and off the beaten path. Earl and his best friend and co-host Craig Roland grew up in missionary families in Bangkok, Thailand and call their work philanthropology. Each episode is usually one visit, but they returned to Alabama Village several times over the last two years because they fell in love with the kids, the program and its founders, John and Dolores Eads.

They try to show different sides of an issue and what is behind the problems. That took a little more time here.

After the gunshots, Earl said, "This is a rough neighborhood. Do people like the Eads and Light of the Village make a difference here and why do they stay? Are the embers they give off enough to light fires inside these kids when there are so many dark forces around them? What would happen to these kids if the Eads weren't here? Would their lights go out?"

"Our show asks tough questions because I have learned that there is no hero or villain, no black and white," says Earl. "Doing good is messy. People do right, they do wrong. They surprise you in good ways, they surprise you in bad ways. Kids you pour your lives into are shot and killed. At the end of the day, is this the best we can do?”

Last week was filled with meeting people searching for answers to tough questions and doing the best they can around Mobile.

DeSaavre Paige returned home to Prichard four years ago and recently started community meetings for those who care about the city and want to do improvement projects together. He raised three sons and works at Strickland Youth Center where he is father, stepfather and uncle to kids who need a strong male figure in their lives.

"Helping these kids is helping myself. Isn't that selfish?" he asks. "Like it or not, these kids are our future. We can let them be wild and deal with them tomorrow when they are causing problems or teach them how to be somebody today and care for themselves. All of these are our kids. He may not be mine, but he is mine. That is why I love my job at Strickland. I can catch one or two and turn them around."

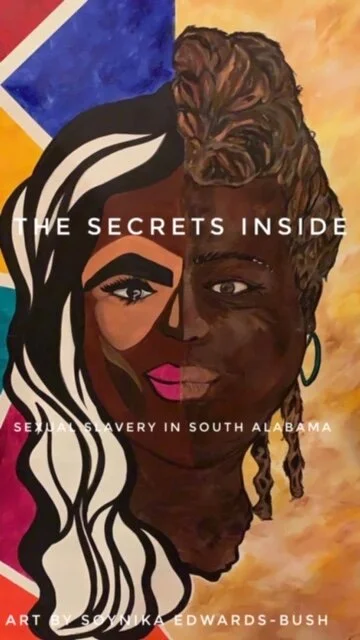

Crystal Yarbrough, director of the new Rose Center in Mobile, is trying to stop the cycle of violence and abuse that exploits girls and forces them into sex trafficking. The drop-in center is part of Eye Heart World and opened in March to create a community and safe place for girls wanting a way out. The Rose Center provides counseling and skills to help girls take care of themselves and learn a better way to love and be loved. Yarbrough, who raised a daughter for years on her own, says God called her to help girls growing up outside of the church. She once thought her ministry would be in the red light district of Amsterdam but realized she could do the same work in Mobile.

"The state of our girls and their loss of innocence way too early in life breaks my heart. So many girls have lost hope," she says. "We can't keep pretending that sex trafficking isn't happening in Mobile. It is a big problem that many people don't want to hear about. If we don't do something now, it will just get worse and we will lose more girls."

Niss, came to Mobile from the Ivory Coast in Africa for security and education. He graduated in May from the University of Mobile with an MBA and is looking for a job in accounting. He wants to give back to the city that gave him a better, safer life.

"Mobile has changed so much in the eight years that I have gone to undergraduate and graduate school here and I don't want to leave," he says. "A lot of internationals come here for school, fall in love with the city and want to stay, but getting a job is difficult for us because we need a sponsorship and someone to give us an opportunity. If I get mine, then I will help someone else get theirs."

Karlos Finley, a lawyer and municipal court judge in Mobile, comes from a family who went to jail fighting for rights and opportunities for African Americans. Karlos says the most important part of his job is speaking to kids about the opportunities they have through education and warning of the punishments and consequences he sees first hand.

“I tell kids they have to respect themselves,” he says. “The tool you think is working for you does not work for you. Once you put a price on something, that is about how much it is worth. My parents instilled a sense of self worth in me and I didn't need another person to affirm who I am. I think that is missing in our society. We need to help young ladies and young men understand that they are priceless.”

For the third time this week I heard, "These kids belong to all of us. They are yours and mine. We are responsible for them."

John and Dolores Ead couldn't have kids of their own so for 16 years they have made the kids in Alabama Village their family. After Mayo was killed, they added his picture to the memorial wall of those who passed away too soon. The pictures remind the couple of why they are here and what is lost when the light of a young life goes out.

The Good Road’s story ends with Jesse giving John a thank you letter before he leaves for college. Jesse has been in the program since he was five years old and John says a letter like that from one of their kids leaving for a better life is the reward for everything they do. These are the moments when they know they are making a difference.

“We are giving this story a happy ending, but who knows what will happen to Jesse," says Earl. "Will he be able to make it outside in a different environment with kids who grew up differently than he did? The odds are against him, but I hope he makes it. Days like this are when the light shines bright."

Jesse. Mayo. Girls being trafficked for sex. An international graduate student searching for his home and opportunity. These are kids in Mobile and they belong to all of us.

It is time to share our light and stop life from being way worse for our kids. At the end of the day, they deserve the best we can do