Oaklawn Cemetery is Mobile's Forgotten Burial Ground

Lee Franks mows the lawn over 400 gravesites at Oaklawn Cemetery every two weeks, but no one buried in those graves is related to him.

Caring for the burial plots started three years ago when he saw his elderly neighbor rolling a lawnmower to his car.

“He was about 88 and caring for the graves of his parents and brother in Oaklawn,” Franks said. “He has a pacemaker and had open-heart surgery. He is also a veteran. I didn’t want anything happening to him.”

Lee Franks/Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Franks mowed the three graves and a couple more on either side. Then he mowed a few more and a few more. He now has a small crew of volunteers bringing their own equipment out to the Mobile cemetery twice a month.

None of them are paid to do it.

Located across the chain-link fence from the well-tended Catholic Cemetery on Martin Luther King Avenue, Oaklawn is an overgrown, forgotten burial ground for Blacks in Mobile. Most of Oaklawn’s 18.5 acres was established in the 1930s and 1940s with simple gravestones facing east. Death, like life, was segregated for many buried here.

Oaklawn’s 10,000 graves share the history of Jim Crow, world wars and civil rights. Buried there are Tuskegee Airmen, Buffalo Soldiers, activists, community leaders, business owners, musicians and Mobile’s first Black doctors, educators, and Mardi Gras Queen. They fought for voting rights, changed the structure of Mobile city government and founded what is now the Mobile Area Mardi Gras Association.

Photo by Lynn Oldshue

A former procurement officer for the Mobile County Commission, Franks said he thinks about each person buried in that ground as he pushes his lawnmower past headstones with the names Fortune, Minor and Sigler. They were a saxophonist who retired from Gayfers after 25 years; a beloved wife, mother and grandmother; and a couple married in April 1941, nine months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

“Oaklawn is the history of Mobile, but most people don’t know about the cemetery or who is buried here,” Franks said. “These people shaped who we are today.”

Oaklawn is non-perpetual care, meaning family, not the cemetery, is responsible for the upkeep of each burial plot. These plots declined over time as caretakers died, moved away or just quit coming.

Photos by Lynn Oldshue

Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Cemeteries are difficult to maintain, Franks said. Without consistent mowing and trimming, the land turns wild. Headstones get covered by vines and weeds or upended by the roots of trees.

“It became almost impossible to get into Oaklawn,” he said. “I hope by clearing these graves, we are helping families find someone they love.”

Those in the homes surrounding Oaklawn said that starting in the 1990s, the cemetery became so overgrown they could no longer see in. The only people entering Oaklawn were dumping trash, selling drugs, burning cars or having sex. The neighbors called the main path into the cemetery “Hooker Alley.”

Photo by Lynn Oldshue

It was not how Oaklawn used to be, said Faye Crosby, who grew up on Whitney Street on the side of the cemetery. She said when she was a kid, the cemetery was “a garden, a park that neighborhood children skipped through on their way to school.” They picked blackberries in the cemetery in the summer and pecans in the fall. Families came on Mother’s Day and Father’s Day to place flowers on the graves.

Crosby said Oaklawn tells the story of Mobile’s Black community, of segregation from birth until death. It’s also a story of love and determination and people who refused to be pushed aside.

“The mothers in our neighborhood were housewives, and the fathers were plumbers, carpenters, electricians or worked at the docks or Brookley Field,” Crosby said. “We were baptized and married in our neighborhood churches. Many were buried at Oaklawn.”

As she got older, Crosby said, the burials at Oaklawn got harder.

“I was a teenager when they started bringing home soldiers from Vietnam,” she said. “We watched the burials with 21-gun salutes and flags draped across coffins.”

Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Crosby estimated 10 boys from her neighborhood went to war, including her brother. All returned home alive, but the nightmares followed them. Her brother refused to talk about it.

“It hurt to see those young guys buried at Oaklawn,” she said. “It also hurt to see the condition their graves fell into, like their lives didn’t matter. Oaklawn became out of sight, out of mind.”

By then, no one claimed ownership of the cemetery. Oaklawn Memorial Cemetery Inc. owns Oaklawn Memorial Cemetery, but ownership of the corporation is unknown. Tax records for the state of Alabama and the Mobile Revenue Department show two different owners. Both denied ownership and have had nothing to do with the cemetery or its upkeep.

But some families and neighbors spoke up about the condition of Oaklawn, causing Mobile Environmental Court Judge Holmes Whiddon to hold proceedings in the middle of the street in front of the cemetery in 2011.

“Evidence showed Bishop Cornelius Woods owned the cemetery,” said Court Clerk Carol Brown, who worked on the case with Judge Whiddon. “We had several hearings to determine if Woods was responsible. He never admitted ownership but eventually paid the fines and cleaned up the cemetery to the city’s satisfaction.”

Cheryl Washington reported on the condition of Oaklawn in 1996 in the Mobile Press-Register. She wrote Woods operated Oaklawn and owned Memorial Funeral Home. He said he couldn’t predict the future of Oaklawn Cemetery, “but the signs don’t look good.” If the families don’t come in, he said, the graves remain uncared for.

Washington wrote, “Although Woods says it’s not much of a problem now, he thinks it will be one day.”

Bishop Woods died in 2018. Michael Strickland, the lawyer for Woods’ wife, Mary Woods, said Memorial Funeral Home has no ownership of the cemetery. There are still a few burials made in family plots, but the question of ownership and responsibility is unclear to this day.

For two years, Jim Ellis, retired director of South Alabama’s Office of International Education, and his wife, Georgeann, have researched the history of Oaklawn, clearing and documenting graves before entering them into the Find A Grave website, a free resource for families and the community.

Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Ellis said 8,288 memorials from Oaklawn have been entered, including more than 800 veterans. But there’s still much of the cemetery that hasn’t been cleared and graves that haven’t been found.

“The back half is so grown up that it’s impossible to get through,” Ellis said. “It goes down to the edge of the floodplain associated with the creek. There’s no telling who is buried back there.”

Ellis dug through library records as well as probate archives and contacted funeral homes and government agencies researching the ownership of Oaklawn. He found deeds showing the land was originally owned by Theophilus Lindsey Toulmin, the son of Harry Theophilus Toulmin, a Confederate Army colonel who became a district judge for the Southern District of Alabama. The area became known as Toulminville and was annexed by Mobile in 1945.

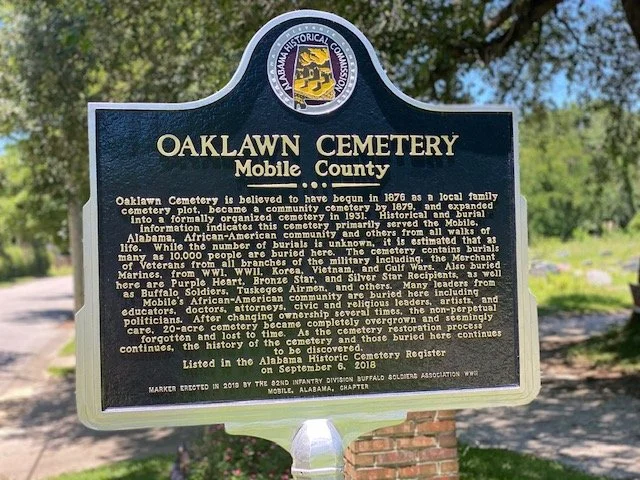

The historical marker placed in 2019 at the entrance of the cemetery explains Oaklawn is believed to have started in 1876 as a family burial site and expanded into a community cemetery by 1879. It became a formally organized cemetery in 1931, serving “the African American community and others from all walks of life,” according to the marker.

Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Determining the ownership of Oaklawn is important, Ellis said, but the bigger story is the people who are buried there.

“These are people who have contributed to Mobile and the nation while struggling in their everyday lives,” he said. “These lives matter today. This is our history and inheritance.”

One of the cemetery’s oldest identifiable graves belongs to Caleb Lewis, who was buried in 1917. There are also his family graves from the 1920s around him.

Photo by Lynn Oldshue

One of the most famous residents of the 89-year-old cemetery is Charlie Foxx, a songwriter, singer and producer, who toured the world with his sister as the Inez and Charlie Foxx Singing Duo. They recorded “Mockingbird” based on the lullaby “Hush, Little Baby.” It reached No. 2 in the U.S. Top Black Singles/Rhythm & Blues chart and No. 7 on the U.S. Popular Music Singles chart in late summer 1963. In January 1998, Foxx was diagnosed with leukemia and died in Mobile.

There are memorials to mothers. One burial vault was painted blue with angel wings and the words, “Mom, if tears could build a stairway and memories a lane, I’d walk up to heaven and bring you home again.”

Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Another mother’s vault was inscribed, “Because of your love, prayers and unyielding desire for excellence, we thank you,” followed by the names of her children and grandchildren. Besides almost every name are the initials: B.S., M.D., D.D.S. or Ph.D.

Oaklawn tells the story of people who opened schools and a branch of the Mobile Public Library for the Black community. There is a mother who raised one of America’s greatest baseball players, Satchel Paige. Others owned restaurants and drug stores on Davis Avenue.

Leon Roberts, member of the Tuskegee Airmen /photo by Lynn Oldshue

It tells the stories of men who won Purple Hearts, as well as men who liberated Nazi death camps, supplied Allied forces with the Red Ball Express and helped General Patton seize Berlin. They returned home from war, only to still be treated as second-class citizens.

They were forced to drink from separate water fountains and sit in the back of city buses. They weren’t allowed to shop or work on Dauphin Street or watch movies at the Crescent Theater.

“So many in the cemetery developed professional lives and businesses despite segregation and Jim Crow,” Ellis said. “Along with the military service, these were the agents of societal and generational change.”

Dr. Yvonne Kennedy, former Alabama State Representative and President of Bishop State Community College/Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Ellis listed several of those agents of change: Dr. Maynard Foster, John Finley, Mattie Blount, Dr. Yvonne Kennedy, Dr. Jerry Pogue, Wiley Lee Bolden, Isaac White and Josephine Allen.

“They fought for equality, voting rights, good jobs and better education,” Ellis said. “They integrated schools and hospitals. Their contributions can’t be forgotten.”

Grave of Dr. Maynard Foster/Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Foster is buried with most of his family in the cemetery. The top of his gravestone described him as a “husband, father and community servant.” The inscription at the bottom reads, “What I spent I had, what I kept I lost, what I gave I have.”

Sometimes visitors to Oaklawn say “he delivered me” as they walk past his grave.

“Dad went to Dunbar High School. He was a boxer and he played football,” said Maynard’s son, Dr. Kendal Foster. “His nickname was ‘Pop Duty,’ but most people called him ‘Pop.’ He went to Tuskegee College during the war. He learned how to fly a plane and became a Tuskegee Airman. But he didn’t like planes, especially the biplanes they trained on. Many of the Tuskegee Airmen became doctors, lawyers and engineers.”

Dr. Maynard Foster went to Meharry Medical College in Nashville and was the first African American to be admitted as an intern at the Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich.

After graduation, Foster returned to Mobile in 1952 and opened his practice, delivering babies and performing minor surgeries. However, Black doctors were prohibited from admitting patients to area hospitals.

“Jim Crow in Mobile meant living and working in apartheid,” Kendal said. “Dad was successful, and he saw patients from early in the morning until late at night, but he couldn’t practice at Providence Hospital, Mobile Infirmary or Mobile General Hospital. Black physicians weren’t accepted in the American Medical Association, a prerequisite for working in hospitals.”

Maynard filed a lawsuit against Mobile General Hospital for the denial of admission based on racial discrimination. After years of legal battles and assistance from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), he won the suit, opening hospitals to Black doctors and nurses.

“The Civil Rights Movement was different in Mobile,” Kendal said. “This was the last place in Alabama to desegregate hospitals, schools and department stores. Dad’s lawsuit was for principles. The principle was that if you take federal monies, it has to be nondiscriminatory.

“The fight for desegregation was hard on my dad and lost a lot of money over it. He died in 1977 when he was only 54.”

Kendal described his father as “courage up close,” a line taken from the USS Alabama billboard that once featured a picture of his father in his Tuskegee Airmen uniform.

Like hospitals, funeral homes and burials were also segregated. The White funeral homes refused to accept or embalm deceased African Americans.

Funerals and burials became an attractive business for Black entrepreneurs in Mobile and across the South. Pearl Johnson opened the Christian Burial Benevolent Association in Mobile in 1924 and became one of the first female Black business owners in Alabama. Almost 100 years later, the burial association is still located on North Hamilton Street.

Funerals weren’t inexpensive, said retired Maj. Gen. Gary Cooper, Johnson’s great-nephew.

Burials in the 1940s and 1950s cost about $500, equivalent to almost $10,000 today, including the casket. Many families paid 25 cents each week for burial insurance.

“Our goal was to ensure everyone had access to burial insurance,” Cooper said. “A few of our customers lived in an area called Hickory Street, home to the poorest of the poor in our community. They brought in their quarters every week.

“That shows how important burying loved ones with dignity was to Black families. They wanted the best funeral they could buy.”

Major General Gary Cooper/Photo by Lynn Oldshue

Cooper was once asked if he would be interested in buying Oaklawn Cemetery. He declined.

“The place is way too big to not have perpetual care,” Cooper said. “Who is going to pay to keep it clean?”

Cooper said he admires and supports the groups trying to keep up Oaklawn, because his father, AJ. Cooper, is buried there.

“My father tried to integrate Mobile’s Catholic schools for a better education for my siblings and other families,” Cooper said.

After several confrontations and an unsuccessful attempt by A.J. Cooper Sr. to get a younger son enrolled at McGill-Toolen, the Cooper children were banned from any Catholic school in the diocese.

“My dad went downhill at a rapid pace after that,” Cooper said. “The fight for integration and a better education for his children broke him at his core. As a result, I came home to take over the business.”

Ellis said that despite the legacy of those buried in Oaklawn, the cemetery became “essentially abandoned and forgotten by the 1990s as the business maintenance model failed.”

“Families moved away and communities changed,” Ellis said. “But Oaklawn remains with graves buried in the grass and headstones peeking out from the shifted ground, asking us to find out more.”

The ultimate question is who is going to take care of the cemetery, Ellis said.

“How are we going to save our history?”

(This story first ran in Lagniappe in November 2020)

Photo by Lynn Oldshue