Change Came to The Avenue

Fisher’s Alley. Jay Bee’s Hardware. Mary’s Grocery. The Lincoln Theater. Besteda Taylors. Central High School.

They were familiar names on Davis Avenue, called The Avenue by locals, but they’re long gone.

Renamed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue in 1986, little remains of the Mobile street that once had “everything here.”

Gone are the clubs and auditoriums where Fats Domino, Aretha Franklin, Etta James and The Drifters played.

Best Grill no longer serves oyster loaves or fried chicken with mac and cheese, green beans and cornbread. There are no more chitterling dinners at Locketts or hamburgers at George’s Playhouse, no more lines for Babe’s Hotdogs that were steamed, not boiled, and covered in special sauce.

Older men no longer play Pokeno and spades in front of stores.

Couples no longer dress to the nines and crowd the sidewalks on Saturday night.

Neon lights no longer hang from clubs and diners in the area once described as “Mobile’s Little Harlem.”

The Avenue was born during Reconstruction as a safe place for Black people to live and own property. As the population grew, Davis Avenue prospered through entrepreneurship and community, despite the restrictive laws of Jim Crow.

But that economically independent community collapsed with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, urban renewal, integration of schools and families moving away.

Those who grew up on The Avenue gave additional reasons for its decline: the closing of Brookley Field, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the opening of shopping malls, racism, crime, drugs and blight.

A few barbershops and funeral homes remain open, but parking lots and empty fields sit where there used to be dry cleaners, corner stores and bakeries. On some blocks, concrete foundations and tiled floors are all that are left behind.

Historic Markers from The Dora Franklin Finley African-American Heritage Trail and photographs from the University of South Alabama archives provide reminders of where shops, law offices, taverns and a cigar maker used to be.

“Many of the buildings were purchased and torn down with money provided by the urban renewal program,” said Eric Finley, who grew up on Davis Avenue. His father, John Finley Jr., opened Finley’s Drug Store No. 1 in 1950.

“They bulldozed the buildings and cleared the land, but they didn’t renew or improve anything,” Finley said. “It is hard to imagine what Davis Avenue used to be.”

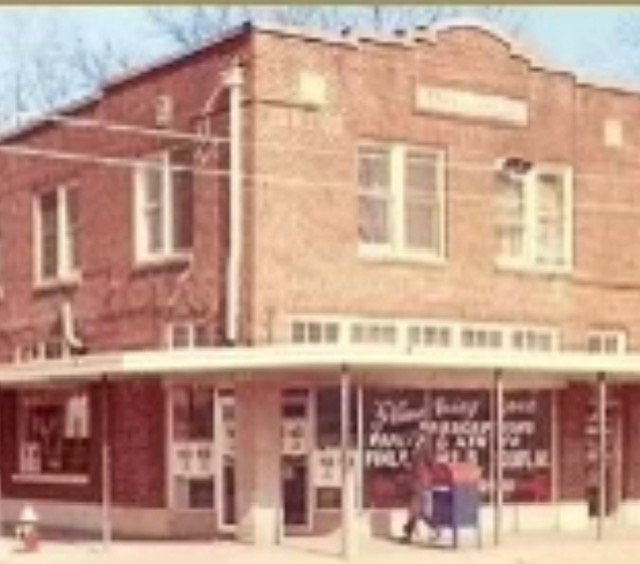

One of those buildings belonged to Finley’s grandfather, James Franklin, a family physician. On the bottom floor was Finley’s Drug Store No. 3, owned by John Finley’s brother, James. Also in the building were the offices of Dr. Franklin; as well as John LeFlore, founder of the Non-Partisan Voters League; and attorney Vernon Crawford, who worked most civil rights cases in Mobile.

The Franklin Building (Photo Courtesy of Eric Finley)

The Franklin Building was torn down circa 1970, said Karlos Finley, James’ son and Eric’s cousin. In its place is a parking lot for Stone Street Baptist Church.

“Those four men were legends in Mobile's Civil Rights movement,” Finley said. “The Franklin Building should be standing today as a part of history.

“If you want to destroy the morale of a community, erase the accomplishments of men like my father,” he said. “The city tore down what the Black community built and pretended like it never happened.”

”You can’t get that history back.”

Tearing down those buildings was a part of urban renewal. Started by the Housing Act of 1949, it was the government’s attempt to address the decline of urban housing across the country. It provided federal loans and grants to help cities acquire and clear slum areas. There was also federal funding for new highways and interstates.

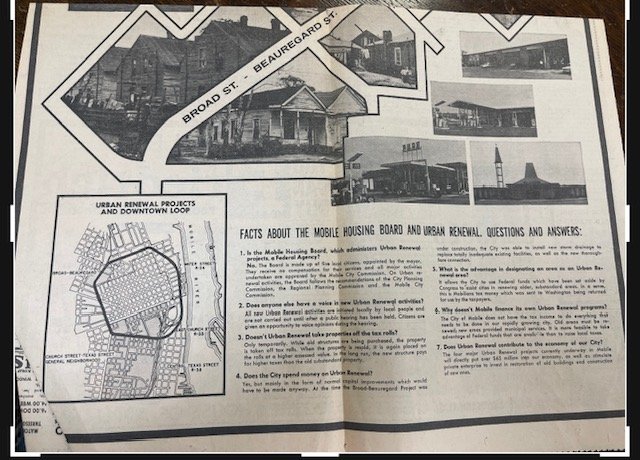

Full-page in he Mobile Press-Register explaining Urban Renewal

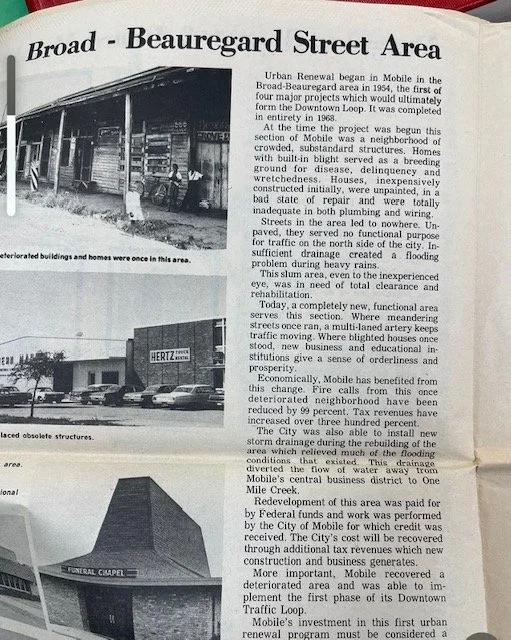

Mobile wasted no time embracing what some people nicknamed “urban removal.” In 1949, downtown was divided into four sections, and the goal was to replace blighted structures with new construction.

The four districts, Broad Street-Beauregard Street connector, Water Street, East Church Street and Central Texas Street, also became part of the Downtown Loop thoroughfare for faster routing of traffic around downtown.

Full-page in he Mobile Press-Register explaining Urban Renewal

The Mobile Press-Register reported in 1957 that the Mobile Housing Board acquired 48.5 acres, including existing streets and alleys, for the Broad Street-Beauregard Street connector- most located in the Davis Avenue area. Structures described as “a breeding ground for disease, delinquency and wretchedness” were demolished and removed from the site as soon as they were vacated. The lots were to be cleared and sold for commercial use.

It was anticipated by the Housing Board that “businesses such as department stores, supermarkets, specialty shops and restaurants will be established in the area by private developers.”

The federal government funded two-thirds of the project with one-third coming from Mobile in the form of cash or improvements, according to the Press-Register. The Mobile Housing Board used appraisals by Mobile realtors to “offer prices that were fair and just, attempting to acquire all property by friendly negotiation.” Otherwise, it resorted to condemnation through the courts and eminent domain.

The Mobile Housing Board records archived at the University of South Alabama include appraisals from Davis Avenue. A data report from 1978 described the neighborhood as “residential with a great majority of the dwellings being considered substandard. The price range varies from $6,000 to $30,000.” Commercial property on the south side of Davis Avenue was appraised at $5,000 for 5,000 square feet. Another property was $1.57 a square foot.

After the completion of the urban renewal projects, Press-Register reporter Ralph Poore explored the question of their effectiveness. In his story “Urban Renewal Successful Except for Private Input,” published on July 26, 1980, he wrote that “the urban renewal program begun 29 years ago has forever changed the face of Mobile. Judging by the removal of the slums, which once encircled downtown, the program was a success.”

But he also wrote, “That same judgment can’t be rendered by the political promises that urban renewal would spur private investment in the area. Private investment in downtown was slow because as Mobile was undergoing urban renewal, it was expanding west with thousands of acres of cheap, virgin land. Ironically, the city expected the same people who allowed the slum conditions to develop to pour their money into improvements downtown.”

40 years after writing that story, Poore remembers sitting in the meetings of the Mobile City Council and Housing Board as they discussed urban renewal. He was a preservationist and felt the city had destroyed too much.

“The Housing Board cleared out the slums, which is exactly what it was supposed to do,” said Poore who now lives in Boise, Idaho. “The unintended consequence was setting up a permanent zone of poverty that still exists today.”

There was no plan for investment or economic development when the buildings came down, Poore said. Black business owners on Davis Avenue did well serving their community, but “because of racial attitudes, they couldn’t get the capital to branch out and create more jobs. Banks didn’t make loans to those neighborhoods.”

Another setback was the closure of Brookley Air Force Base in 1969. About 13,000 civilians lost their jobs in the largest base closure in American history. Many of those lived and shopped around The Avenue.

By the late 1960s, Davis Avenue was in decline, and urban renewal gave it a different appearance, said Paulette Horton, author of the book “Avenue,” which chronicles the history of Davis Avenue from 1799 to 1986.

“So much was pulling people away from The Avenue,” she said. “The Civil Rights Act gave them the right to go anywhere, and better transportation made it easier to get there. They shopped at the new malls and moved into white neighborhoods, such as Toulminville, taking dollars away from the Avenue. Some moved north for better jobs and better lives.”

The assassination of King on April 4, 1968, was the last straw, Horton said.

People were angered by his murder and marched on Davis Avenue, she said. They damaged stores with bricks and firebombs.

“It went downhill after that, and The Avenue never came back,” she said. “Clubs became known as slaughterhouses because of shootings and stabbings. Businesses closed earlier and crowds stopped coming by.”

Jay Bee’s Hardware, owned by J.B. Friedlander, was one of the stores burglarized multiple times.

“Daddy was over there forever, but during the Civil Rights era they gave him a lot of grief, and he started getting robbed,” said Donnie Friedlander, J.B.’s son.

“He was once robbed after he came back from the bank,” Friedlander said. “Dad had $2,000 in fresh bills in his pocket. They laid him and mom out on the floor. She never went back to the store. By then, business was bad, but Daddy loved the community and kept going over there until he was bought out with urban renewal money.

“I think the city paid him $10,000 or $20,000 to relocate, then they tore the building down.”

Florence Howard Elementary was built in 1998 between Pearl and Cherry streets, where Jay Bee’s Hardware used to be.

“Crime and blight were part of the decline, but racism was another reason they tore those buildings down,” said Friedlander, who is a lawyer in Mobile.

“The powers that be didn’t give a damn about the history of The Avenue.”

The later generations who grew up on The Avenue didn’t have much interest in our community or neighborhood history either, said Mary Morris, an activist during the Civil Rights era. She has also been a beauty shop operator on Davis Avenue for 60 years.

Mary Morris

As the older generations died out, the younger ones didn't stay to take over what was left, she said. They just moved away

“The oldies like Yvonne Kennedy and I fought to keep businesses on The Avenue, but we didn't have the support as our people had in Birmingham and Montgomery,” she said. “Davis Avenue lost its base, and there weren't enough people fighting for it to remain.’

Integration also took a turn, Morris said. The city restructured Dunbar Middle School. They also closed Owens and Northside elementary schools and Central High School, “sending our students and best teachers outside of our district.”

“Our teachers lived in our neighborhoods and worked closely with students and parents,” she said. “Most of my clientele were teachers with master's degrees and PhDs. They were a good influence in and out of the classroom. Now the children stand on the corners early in the morning, waiting to be bused to schools outside our neighborhood.”

“There are lessons to learn because losing this community was losing our strength,” Morris said. “We lost schools, neighborhoods, businesses and churches. We became unrooted and unconnected.”

What happened on Davis Avenue happened across the country, said Alvin Hall who came to Mobile in 2019 while driving from Detroit to New Orleans and recording his recently released podcast “Driving the Green Book.”

Photo courtesy of Alvin Hall

“There were these streets in every town,” Hall said. “There was Davis Avenue in Mobile; Fourth Avenue in Birmingham; Jefferson Street in Nashville, Tennessee; and Farish Street in Jackson, Mississippi. Most of them were either obliterated by urban renewal or they became isolated when the government built the highway system. Both led to their economic demise.”

“But if you look at many of the places targeted by urban renewal, they weren’t all slums,” Hall said. “They were also middle-class and upper-middle class areas. Why were they targeted for urban renewal? It was to deal an economic setback to the African-American community and to get those dollars into the white businesses.”

Most white people had never been to black communities because of segregation and Jim Crow, Hall said. They only saw images of poor housing that needed removing. They didn’t see the parts that were middle- and upper-middle-class housing or business districts.

“Segregation and Jim Crow gave the public a cover, so they could say they didn’t know what was being destroyed,” he said.

Hall and his producer, Janée Woods Weber, spent a day and night in Mobile.

“Mobile has a Southern gracious quality, but the lines between black and white are still there,” said Hall, who grew up in a rural area near Crawfordville, Florida.

As Hall rode with Eric Finley along Martin Luther King Jr Avenue on the Dora Finley African-American History Tour, he was surprised that the renewal in other parts of Mobile hadn’t reached there.

“It was disappointing to see an area with this much history still left behind,” he said. “As outsiders, we wondered if anyone cared about what happened here.”

There have been revitalization attempts for Martin Luther King Jr Avenue, but the most promising efforts are happening today.

One is the Broad Street Redevelopment that is currently adding space for pedestrians, cyclists and landscaping. Mayor Sandy Stimpson said the project touches areas that have needed repair and upgrade for decades, while also reconnecting neighborhoods divided by the street’s seven-lane expanse.

“We know these areas were impacted by projects in the 1960s that occurred under the banner of urban renewal,” Stimpson said. “By creating inviting gateways for pedestrians and using smart street design, we hope to draw people back into these areas in the heart of our community. We are creating a cohesive street network, connecting multiple neighborhoods to major economic engines and employment centers in our city. “

Improvements to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr Avenue are scheduled to begin in 2021. They will also be part of the redevelopment eventually connecting Broad Street to the Three Mile Creek Greenway trail.

Another effort is from The History Avenue Foundation and the Fuse Project to invest in the education, housing and wellness of the neighborhoods around Martin Luther King Jr Avenue.

Fuse started this work three years ago, said Freddie Stokes, Executive Director of the History Avenue Foundation. Within five years Stokes hopes the foundation will break ground on mixed-income housing and have the early learning center in place.

“We're not trying to create anything on The Avenue that it hasn’t seen before,” he said “The people who are close to the problem and the pain must also be a part of the solutions and the power to create change.”

Jocelyn Banks

Jocelyn Banks lived through painful years of change during the late 1960s on The Avenue. She was the fifth child in her family to attend Central High School before integration closed the school in 1970. She was bused to Murphy High School her junior and senior years.

“My freshman year at Central, we heard rumors of something about to happen, but we didn't know what,” she said. She was proud to finally be a student at the high school and was a majorette for Central’s band, called the Marching 130.

“Going to school at Central and the activities we were involved in were our heritage and our achievements,” she said. “Those were ripped away from us when they told us we had to leave.

“I cried all summer before I started Murphy for my junior year,” she said. “We were teenagers unprepared for what integration was throwing us into.”

Banks’ mother took her to Murphy her first day because she didn’t want to go.

“My mother told me, ‘you are somebody. Keep your head up and stop looking down’.”

“We always felt less than whites, because that is the way we were treated,” Banks said. “Now we were forced to go to school with students who didn't want us there. But I quickly realized they were just as frightened as we were.”

Integration didn’t go smoothly, Banks said. There were fights and riots. Teachers locked students in classrooms to keep them safe. The national guard was stationed on campus to keep order.

However, some of the teachers were kind and tried to make the merging of students as easy as possible.

“In a way, I am glad that I went to Murphy,” Banks said. “I realized the white students weren't any better than we were, and we all had our own problems.”

There are lessons from Davis Avenue, integration and her mother that stayed with Banks the rest of her life.

“My mother and many others who kept The Avenue going are buried in Oaklawn Cemetery, but those of us still alive can pass their stories down,” she said.

Those stories were buried for so long that it’s healing to finally share them, Banks said. She was excited when they started putting up the African-American history markers because she learned a history she didn’t know.

“We have been through so much, and it is finally being recognized,” she said. “We can't let our history go.”

This was the final story in the 4-part series, “Buried at Oaklawn” that ran in Lagniappe in November and December 2020. About 10,000 people are buried in Oaklawn Cemetery, including hundreds of veterans and Mobile’s first Black doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs and educators. Many grew up on The Avenue. Today no one claims ownership of the overgrown cemetery where the graves are filled with the history of Mobile.